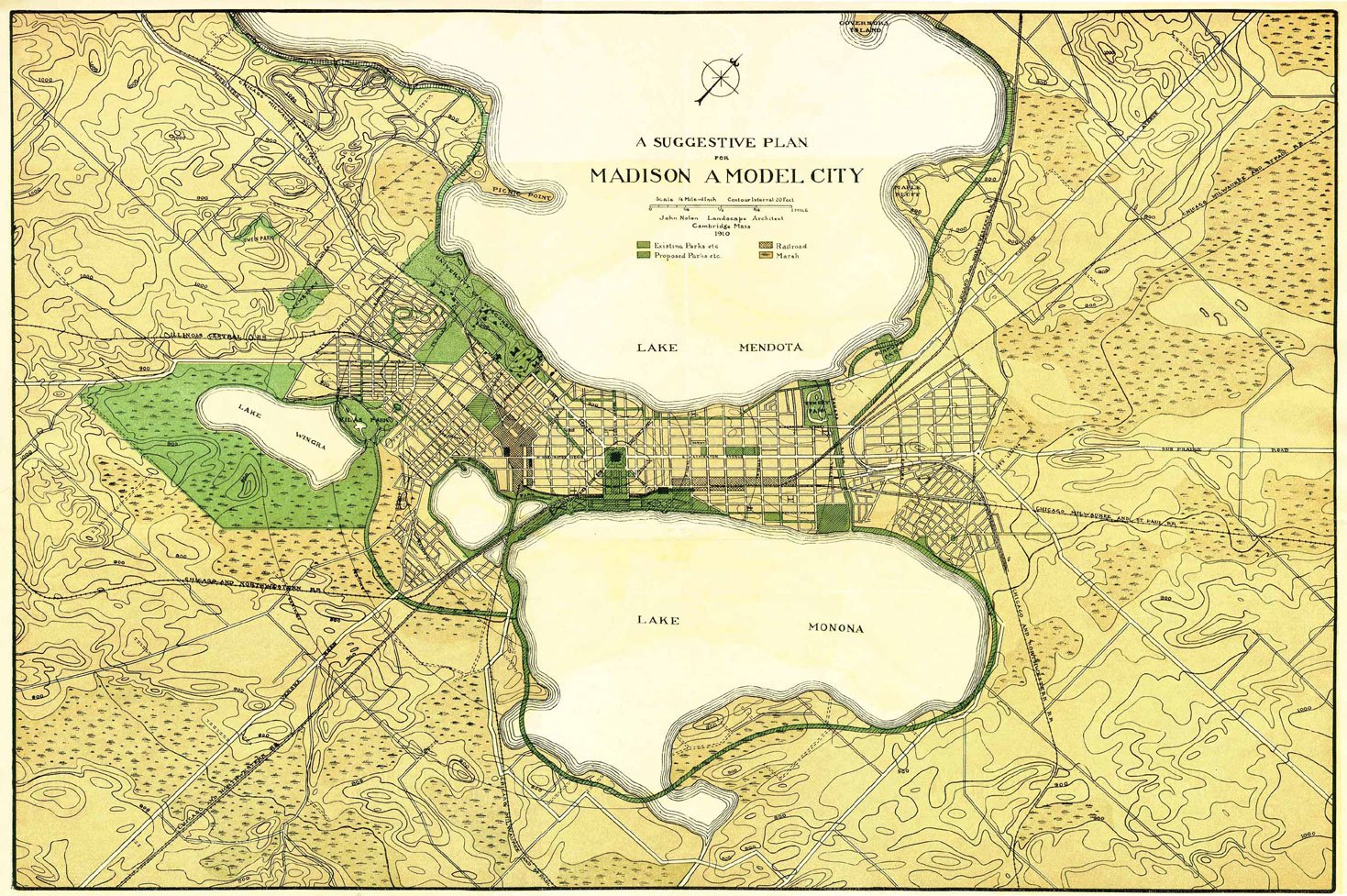

Madison: A Model City

We are just beginning to understand the power of local history to enhance our understanding of ourselves, our cities, and our culture. It is, after all, that stratum of history that touches our lives most closely. David Mollenhoff, a historian specializing in the history of Madison wrote “Madison: A History of the Formative Years” — a classic book on why Madison is the way it is today. His unique interpretive framework emphasizing public policies and community values reveals major themes that flow through time. Following are excerpts from his book regarding John Nolen and the impact he had on our city.

“Meanwhile Olin began making inquiries: who he asked, are the most talented landscape architects in the country? — for the moment sidestepping the question of how he would pay such a person. His audacious goal was to get the best designer in the country to work exclusively for Madison, Wisconsin. From this process, Olin obtained the name of John Nolen, a thirty-eight-year-old landscape architect who had established a highly regarded practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The more he heard about Nolen, the more convinced Olin became that Nolen was the right man — indeed the only man — for the Madison job. Though he had been in practice for only two years, he already had major contracts with Roanoke, Virginia, Savannah, Georgia, San Diego, California, and Charlotte, North Carolina, and was moving in the fast track of an ambitious new specialty known as city planning.

Now came the real challenge: how to get Nolen to forsake the Boston area and his burgeoning practice to come to a small Midwestern community. The problem was particularly exasperating because Olin knew that the Common Council would refuse to pay a penny more than twelve hundred dollars for the job of landscape architect and that Nolen was making at least three times that amount in private practice.

Hamstrung by Nolen's decision to not move to Madison, but with the state funding package still in place, Olin decided to pursue the best compromise and try to get Nolen to do Madison's work as a consultant. However, this required the consent from the toughest funding source of all: the Common Council. Here Olin's challenge was persuading the aldermen that they should pay a man twelve hundred dollars a year to work party-time when Mische had worked full-time for the same amount. Olin regaled the council with Nolen's impeccable national reputation, cited superlative recommendations from past and present clients, and emphasized that landscape architects rarely lived in their clients' communities. Madison would be exceptionally fortunate, insisted Olin, to get a man of this caliber to do all the city's park, boulevard, and cemetery design work. Furthermore, Madison deserved nothing less. Over the strong objections of several aldermen who groused ab out the city not getting its money's worth, the council acquiesced and gave Olin his three-year commitment. Olin got his man.”

John Nolen in his 1911 book, Madison, A Model City, used a wonderful term — “a practicable vision” — to describe his plan. He used that term because he wanted his readers to understand that visionary plans can only be done in stages, but that you must first start with a big vision or you are destined for mediocrity.